PAUL K. SAINT-AMOUR

Countermapping Ulysses

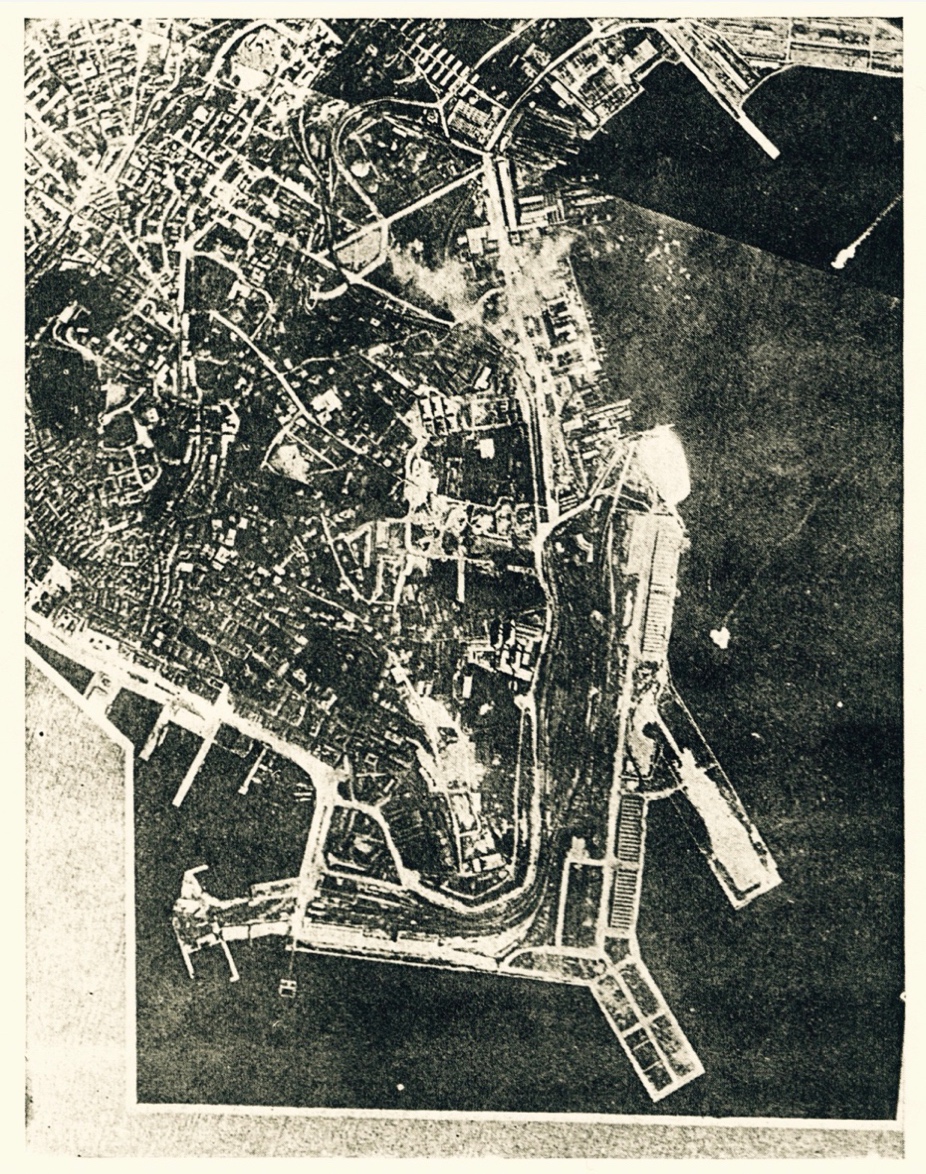

Figure 1.

Aerial photograph of Trieste, 1915. Original caption: “Aerial

bombardment of Trieste. Note falling bombs in center of picture;

and exploding

anti-aircraft shells over the water. Italian official

photograph.” Herbert E. Ives,

Airplane Photography

(Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1920), 30.

Cartographic Unconscious

My epigraph is a photograph—an aerial photo of Trieste (Fig. 1). It was taken by an Italian plane during one of the four air raids that Italy mounted during May and June 1915 as part of a campaign to reclaim Trieste from the Austro-Hungarian empire. If you study it carefully, you’ll see bombs dropping from the plane toward the city where James Joyce and his family were then living on the second floor of Via Donato Bramante, 4. Because of the terrifying commotion of the raids and the partial evacuation they prompted, the Joyces were to leave Trieste in late June 1915 for Zürich, where they would remain until the end of the war. The photo is a haunting and heretofore missing image from the archive of modernist literature.

When I first came across this image in a 1920 manual of aerial photographic interpretation, I was struck not only by its resemblance to maps of Trieste I had seen but also by the gulf between those maps and the photograph. The maps were schematized and information-dense, full of street names and the names of parks, docks, and monuments. The aerial photo, by contrast, was a plan view of the city intended not to facilitate navigation, commerce, or culture-seeking but to document barbarism. Yet it too was full of information, if of a different kind. It documented, for example, the absence of fog or low-lying clouds on the day it was taken; the length of wake left by a boat. And it documented the event of the bombing itself and the anti-aircraft response by the Triestine batteries. Conventional maps aspire, at least, to be abstract renderings of a space that filter out the contingencies and obstructions that might afflict particular moments of seeing. Aerial photographs, in contrast, can readmit those contingencies and obstructions. We could say that such photographs re-subject the map to time. What’s more, they do so in a way that comports with the novel Joyce had begun writing by the time this photo was taken. For however much Ulysses (1922) is engaged with maps and mapping, it is more concerned to portray its target city on a particular day—June 16, 1904—contingencies, obstructions, and all.

Aerial photographs have a reputation for epitomizing the domineering god’s-eye view of militaries, governments, and corporations—for seeing like a state, as James C. Scott puts it.[1] However, studying the history and technical dimensions of aerial photography teaches one how reductive this reputation is. During the First World War, air photos of large swathes of the Western Front were produced by stitching together dozens, even hundreds, of individual images. To produce these “photomosaics,” intelligence workers had to learn to correct each photograph for tilt, scale, radial distortion, exposure, and framing so that it would line up properly with its neighboring images. After the war, former military photographers and map makers were employed by municipalities and private firms to make massive aerial maps of cities using these same techniques (Fig. 2). Although these photomosaics formed the basis for many conventional maps during the interwar period, they belie the conceit of the map in several ways. As against both the atemporal conceit of the conventional map and the snapshot temporality of the single aerial photo, they’re polytemporal: they produce the illusion of simultaneity by compounding images taken hours, days, or weeks apart. They summon the illusion of seamless totality by way of elaborate techniques for rectifying, syncing, and blending. Yet despite these techniques, they contain residues of their scattered temporalities. If resolution permitted us to zoom in to the scale of a few adjacent sections of these images, we’d see shadows leaning in slightly different directions from section to section, or unmelted snow on the ground in one but not the next.

Figure 2.

Aerial photomosaic of the greater New York area made by Fairchild

Aerial Camera Corporation in 1924. The image was assembled from

2000

individual images taken by three planes over the course of

several months.

I have referred elsewhere to aerial photomosaics of the First World War and the interwar period as “applied modernism.”[2] I used the expression for three reasons. First, aerial photomosaics were associated with avant-garde painting during and after the First World War.[3] Second, images such as these shared with much avant-garde painting the premise that distortion was the only route to revelation. And third, the aerial photomosaic partook of a tendency shared by many Western modernisms—literary as well as visual ones—to view the total from the vantage of the radically site-specific, subjective, or fragmentary, emphasizing in the process how portraits of a given totality can be both generated and apprehended only from viewpoints that are optically and ideologically partial. We might say that they understand the total as a special case of the partial rather than the reverse. In calling the modernism of the photomosaic “applied,” I’ve emphasized the practical uses to which the photomosaic was put, in military and urban planning, from the 1910s onward. Here I suggest that in addition to undergirding the city maps of the time, aerial photomosaics were a kind of cartographic unconscious. Even as they were touted for being the apotheosis of mapping, they also displayed what virtually all maps efface: the fact that the view from nowhere is a projection of many views from multiple somewheres, and from multiple somewhens. Inside or beneath the map, we find the countermap.

On Countermapping

In likening interwar aerial surveys to countermaps, I’m borrowing a word that entered the language much more recently, originally in reference to rural rather than urban practices. The term countermapping was coined by the American sociologist Nancy Lee Peluso in a 1995 journal article. Peluso described how Indigenous forest-dwellers in Kalimantan, Indonesia, were appropriating the tools of the powerful—state maps and mapping technologies developed for large-scale resource extraction—to “bolster the legitimacy of [their own] ‘customary’ claims to [forest] resources.”[4] Since Peluso’s article appeared, the term countermapping has expanded to include mapping against dominant power structures in many more scenarios—by non-Indigenous communities as well as Indigenous; in urban places as well as rural ones; and to many different ends beyond securing territorial resource claims. Migration studies scholar Amalia Campos-Delgado, for instance, uses countermapping frameworks to study the cognitive maps created by Central American irregular migrants in transit through Mexico on the way to the United States, reading their maps as disputing the metanarrative of state-centric maps and making visible the physical, mental, and affective experiences of individual migrants.[5] In Los Angeles County, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, in collaboration with the Coalition for Economic Survival, has used Geographic Information System and Los Angeles Department of Housing and Community Development data to produce a time-lapse map of evictions from affordable housing based on Ellis Act statements, in order to demand an amendment of the Act.[6] And in Newcastle-on-Tyne in the United Kingdom, a 2014 participant-led exhibition called “Imaging Homelessness in a City of Care” featured a hand-drawn map of the city incorporating annotations and life-history excerpts by the project’s thirty participants.[7] These disparate-seeming projects share a commitment to mapping for the sake of and often in partnership with the most vulnerable members of a given society. They conceive of map-making as an instrument of reparative or social justice. Even when it deploys the view from above, countermapping is cartography from below.

The syntax of my title configures Joyce’s novel as an object rather than an agent of countermapping. But one of the most compelling things about Ulysses is that it also engages, three quarters of a century before the term was coined, in countermapping. This is something we’ve known since the early 2000s, when Eric Bulson and John Hegglund, independently of one another, published articles on the ironic and decolonizing uses Ulysses makes of Ordnance Survey maps.[8] The Ordnance Survey of Ireland, first conducted by the occupying government in the early nineteenth century, immediately following the Acts of Union (1800), and periodically updated, was an exercise of colonial state power. It anglicized or transliterated Irish place names and was used to update land values for purposes of taxation. Produced at the scale of six inches to the mile—and in even greater detail for urban areas such as Dublin—the Survey made Ireland the first country in the world to be entirely mapped at such a scale. Its putatively high levels of accuracy and detail asserted an epistemological infallibility that was immune to time and that had the ideological function of naturalizing, even perennializing, the British possession of Irish space.[9] We should bear in mind, though, that like the aerial photomosaics mentioned earlier, the Ordnance Survey wasn’t taken in all at once by an all-seeing eye but compiled painstakingly over time, in this case over two decades. From 1825 to 1846, teams of surveyors made many thousands of individual measurements and trigonometric calculations that were then collated to produce coverage of the whole island. Because the final years of the Survey overlapped with the first years of the great famine in Ireland, parts of the project were made almost instantly obsolete by changes wrought by the famine. As Hegglund writes, “Cottages, estates, and even villages were deserted; networks of incomplete ‘famine roads’ were built as public works projects; and larger metropolitan areas such as Dublin and Cork swelled with new public buildings, including workhouses for the waves of destitute immigrants from the countryside.”[10] (The absence of many famine roads from Irish maps, and the haunting of Irish maps by this absence, is the subject of Eavan Boland’s 1994 poem “That the Science of Cartography is Limited,” one of the great lyrics of counter-cartographic memory.)[11] Despite critical omissions like these, the Ordnance Survey continued to be used for many decades as the template for virtually all professional maps of Ireland.

One of those professional maps was the pocket map of Dublin included with the Thom’s Directory for 1904 or 1905, which was one of the maps Joyce used, while writing Ulysses, to trace his characters’ itineraries and to determine when they would intersect. For Hegglund, the Ordnance Survey as Joyce’s book deploys it ceases to be an authoritative and positivist account of the territory it covers and becomes an “object of desire giving rise to projection and fantasy about different possible relationships between geographical space and community […] an aesthetic object that prompts a critical consciousness of spatiality.”[12] Bulson, for his part, sees Ulysses’s internal map-making as an adaptation of the Ordnance Survey “from within,” and as “an act of reappropriation, a way to imagine Ireland as an independent nation in the not-so-distant future with a colonial past.”[13] In both of these accounts, and in subsequent studies by Liam Lanigan and Cóilín Parsons, we see Joyce’s novel doing more than refusing or negating the map. It maps back, bending the Ordnance Survey to countervailing political purposes and exploring the emancipatory potential of alternative cartographies.[14]

What are some examples of countermapping internal to Ulysses? A few are explicitly described by characters in the novel, as happens in “Aeolus” when Myles Crawford tells the story of how Ignatius Gallaher—Joyce’s name for the historical Fred Gallaher—scooped other journalists and evaded the British censors by telegraphing a map of the Invincibles’ escape route in the Phoenix Park murders to the New York World, syncing positions on the map of Dublin to letters on a particular page of newsprint in the possession of the telegram’s recipient. The vignette provides both a practicum in the subversive cartographic workaround and a kind of allegory, as Bulson puts it, of “Irish history waiting to be transmitted.”[15] Ulysses offers humbler conundrums in its countermapping problem sets, too, as when Bloom thinks in “Calypso,” “Good puzzle would be cross Dublin without passing a pub”—a puzzle whose solution required software engineer Rory McCann to develop a special algorithm in 2011, and that dozens of Joyceans and other thirsty flâneurs, cameras strapped to their chests, have reconfirmed since.[16] And the relentless horizontality and hyperlinking of “Wandering Rocks” imply the existence of the very thing that episode withholds: a conventional map of Dublin in which all the episode’s places and toponyms can be glimpsed simultaneously in relation to one another.

Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus Joyce, once boasted of his eldest son, “If that fellow was dropped in the middle of the Sahara, he’d sit, be God, and make a map of it.”[17] The boast cannily brings together cartography, conquest, and the trope of terra nullius whereby settler colonists morally justify themselves by misrepresenting the territory they appropriate as empty or desert. Scholars of Joyce’s countermapping have inverted John Joyce’s portrait of his son, seeing the writer as playing generative havoc with the Sahara maps of the settler colonial state. Much recent work on spatiality in “Wandering Rocks” finds that episode less interested in occupying the cartographic viewpoint than in anatomizing the conditions and operations through which it is produced by way of manipulations of street-level experience, even if that anatomizing process requires the summoning of a phantom cartographer.[18] Actual high-altitude perspectives are in fact scarce in Joyce’s work. The most explicit thematizations of mapping in his writing are from the horizontal perspective of the pedestrian. These passages recruit recognizable coordinates and place names to the idiosyncratic cognitions, affects, and associations of the walking subject, as when Stephen Dedalus, walking to a morning lecture in chapter 5 of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), anticipates reliving the particular aesthetic experience produced in him by the writer he associates with each section of his walk:

The rainladen trees of the avenue evoked in him, as always, memories of the girls and women in the plays of Gerhart Hauptmann; and the memory of their pale sorrows and the fragrance falling from the wet branches mingled in a mood of quiet joy. His morning walk across the city had begun, and he foreknew that as he passed the sloblands of Fairview he would think of the cloistral silverveined prose of Newman; that as he walked along the North Strand Road, glancing idly at the windows of the provision shops, he would recall the dark humour of Guido Cavalcanti and smile; that as he went by Baird’s stonecutting works in Talbot Place the spirit of Ibsen would blow through him like a keen wind, a spirit of wayward boyish beauty; and that passing a grimy marine dealer’s shop beyond the Liffey he would repeat the song by Ben Jonson which begins:

I was not wearier where I lay.

His mind when wearied of its search for the essence of beauty amid the spectral words of Aristotle or Aquinas turned often for its pleasure to the dainty songs of the Elizabethans.[19]

One obvious function of the passage is to ironize Stephen’s internal self-fashioning as the kind of young aesthete who curates his experience of urban space in such rarefied, possibly pretentious terms. But it does more than that. As one of the first protracted instances of countermapping in Joyce’s fiction, the passage takes as its raw inputs the sorts of urban place captured in hyper-detailed plan view by the Ordnance Survey—places of colonial poverty, labor, and environmental degradation such as the Fairview sloblands, a waste mudflat created in the 1860s by the coming of the Great Northern Railways and used until 1908 as the City Dump. Stephen’s mental traversal of those places transubstantiates them into sites of revitalizing aesthetic experience for the colonial artist-intellectual who is able to read widely and feel boldly. A reeking slobland is countermapped as a silverveined cloister.

When Joyce the literary cartographer does take to the air, as it were, it’s not to survey or triangulate or plot coordinates, but to play with other possibilities for conveying a sense of spatial relations and extensivity, even of spatial affect. Take this dusk reverie from the final pages of “Nausicaa,” which interrupts Bloom’s internal monologue to breathtaking effect:

A last lonely candle wandered up the sky from Mirus bazaar in search of funds for Mercer’s hospital and broke, drooping, and shed a cluster of violet but one white stars. They floated, fell: they faded. The shepherd’s hour: the hour of folding: hour of tryst. From house to house, giving his everwelcome double knock, went the nine o’clock postman, the glowworm’s lamp at his belt gleaming here and there through the laurel hedges. And among the five young trees a hoisted linstock lit the lamp at Leahy’s terrace. By screens of lighted windows, by equal gardens a shrill voice went crying, wailing: Evening Telegraph, stop press edition! Result of the Gold Cup races! and from the door of Dignam’s house a boy ran out and called. Twittering the bat flew here, flew there. Far out over the sands the coming surf crept, grey. Howth settled for slumber, tired of long days, of yumyum rhododendrons (he was old) and felt gladly the night breeze lift, ruffle his fell of ferns. He lay but opened a red eye unsleeping, deep and slowly breathing, slumberous but awake. And far on Kish bank the anchored lightship twinkled, winked at Mr Bloom. (U 13.1166–81)

Starting with the last firework shot from Mirus bazaar in Ballsbridge, the destination of the viceregal cavalcade, the reverie touches down at a series of points farther and farther away from Bloom’s location: the nearby Leahy’s terrace, home to St. Mary’s Star of the Sea church, where the men’s temperance retreat has been happening concurrently with Gerty and Bloom’s encounter; the home of the deceased Paddy Dignam, just a few blocks to the east at 10 Newbridge Road; Howth Head, the red lamp glasses in its Harbour Lighthouse giving it the appearance of having one open red eye; and the lightship at Kish bank farther out in Dublin bay. Only a twittering bat could actually visit these places, but the impression the passage conveys isn’t of frenetic motion through the air but of a sensorium in a state of reposeful receptivity, taking in an array of sights and sounds—the lamplighter’s light, the postman’s knock, a newsboy’s cry, a boy’s call—as they travel across different expanses, from different directions, and deriving from them a sense of the city going about its dusk business and of the sea extending darkly to the east. It’s a sensory map but also an affective one, with regions of cozy routine (sheep returning to the fold, letters arriving, lights being lit), of transgression (lovers’ trysts), of melancholy (the last fading firework of the evening), of nostalgia (the “yumyum rhododendrons” recalling Bloom’s memory of making love with Molly on Howth Head years before), and of foreboding (the “coming surf” creeping, grey). There’s even, in the personification of Howth as old, sleepy, and glad to feel the breeze, and of the lightship as winking at Bloom, a sense that the darkening landscape is alive and on warmly personable terms with its human beholder.

In addition, I’d suggest there’s a callback in the passage to an earlier moment of high-altitude description in Joyce’s oeuvre, a kind of intertextual mapping whereby the dusk reverie in “Nausicaa” fills with echoes of the lyrical effects in the final paragraph of “The Dead” (1914):

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.[20]

These echoed effects include incantatory repetition, a devotion to the present participle, and the use of mannered, slightly archaic inversions in word order (“watched sleepily the flakes” in “The Dead,” “felt gladly the night breeze lift” in “Nausicaa”). They include heavy alliteration, especially around soft-consonant words beginning with /f/ (faded, faintly, falling, far, farther, fell, felt, flew, floated, folding, etc.) and /l/ (last, lamp, lay, Leahy’s, light, like, linstock, lit, living, lonely, etc.). And they include the lyrical chiasmus (“falling softly […] softly falling,” “falling faintly […] faintly falling” in “The Dead,” “The shepherd’s hour: the hour of folding” in the “Nausicaa” passage). These similarities in sound and sense effects underscore other convergences. Both passages describe lamplit scenes in which a lone viewer looks out over a darkling prospect deepened by falling flakes of snow or fireworks, imaginatively expanding that prospect over a vaster space than he can see. Both feature space-extending infrastructure (the newspaper, along with the lamplighter, postman, and lighthouses in “Nausicaa”). Reading the passages together, we find prose maps of different geographical terrains referring by way of consonance and rhythmic accord to the same third affective landscape. This is one way literature may map against the grain.

Yet the differences between the two passages are also striking. In “The Dead,” Gabriel Conroy has missed a sexual encounter with his wife Greta, despite being in physical proximity to her, while she has been remembering a youthful love affair with the deceased Michael Furey. In “Nausicaa,” Bloom has experienced a sexual encounter with the stranger Gerty, despite not being in physical proximity to her, while his wife Molly has been commencing a present-tense love affair with the too-lively Blazes Boylan. Gabriel’s passage faces westward, toward death. Bloom’s faces eastward, toward night and sleep but also toward the promise of dawn. We might not go as far as to say that the passage from “Nausicaa” redeems the passage from “The Dead,” but it does revisit it, revising it gently as comedy. And it does so by bringing one highly idiosyncratic cognitive map of Ireland into relation with another, both of them sprinkled with geographical features and place names, but one inclined toward emptiness and violence (the “mutinous” waves and thorns and “spears” of gates), the other toward plenitude and a whimsically anthropomorphized landscape. If this is the way Joyce maps the Sahara of marital relations and their limits, or of an island awaiting the political form of the nation state, it’s from a conspicuously imaginary viewpoint projected by a viewer who is full of affect and memory. Although these Joycean countermaps engage in something like triangulation, the fixed points from which they begin do not have terrestrial coordinates.

Emergent Countermaps

Having elaborated on some recognized instances of countermapping in Ulysses, I turn now to two lesser-known types that deserve more attention. The first type asks an Irish Studies approach to Joyce to learn from work in the fields of Black geography and Indigenous Studies, in particular from certain itineraries and spatial adjacencies connected with Black exilic thought in dialogue with Indigenous theorists and movements. In his classic 2003 study Black Like Who?, Black Canadian cultural studies scholar Rinaldo Walcott describes the always-diasporic politics of Canadian Blackness in a way that scrambles territorial maps:

In a Canadian context, writing blackness is a scary scenario: we are an absented presence always under erasure. Located between the U.S. and the Caribbean, Canadian blackness is a bubbling brew of desires for elsewhere, disappointments in the nation and the pleasures of exile—even for those who have resided here for many generations.[21]

By placing Canadian Blackness between the United States and the Caribbean, Walcott suspends it between histories of Atlantic slavery in which both the United States and the Caribbean were primary destinations for enslaved people. He marks Canadian Blackness, too, as “an absented presence always under erasure,” at risk of disappearing between the more voluminous discourses around Afro-Caribbean and African American history and identity. And most noticeably, he makes Canadian Blackness, rather than Canada the territorial nation-state, the meeting point between various periods of Black immigration from both the United States and the Caribbean, and a potential site at which to “invent traditions” for bringing different generations of Black diasporic subjects into conversation with one another.[22]

In her recent book The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (2019), Tiffany Lethabo King takes up Walcott’s way of locating Black Canada’s diasporic politics “between the U.S. and the Caribbean.”[23] For King as well, that “between” speaks not only to Black Canada’s state of erasure but also to its being a point of linkage, even of centrality:

The betweenness of which Walcott speaks, or this space of displacement, rearrangement, and suture, forces a rereading of the map of the Americas as well as a rereading of Black diaspora studies. Walcott’s rearrangement is an explicit challenge to the traditions of centering either the United States or the Caribbean in the field by establishing Black Canada as a crucial nexus.[24]

King writes that as an African American raised in the tristate area of the Delaware River Valley, she was unused to seeing Indigenous peoples in coalitions with other radical people-of-color groups. Yet in Toronto she found that “Resisting the Canadian project of Indigenous genocide and colonialism” was “a part of the pulse of Black radical politics.” In thinking about the conditions of possibility for this coalition, King focuses on Black Canadians’ “acute diasporic sensibility of being in exile,” their refusal to “seek a comfortable resting space in the Canadian nation-state.”[25] That flexible, deterritorialized orientation to home, so vividly mapped by Walcott, proved compatible, she found, with Indigenous communities’ understanding of land as “a meaning-making process rather than ‘a claimed object,’” and of sovereignty not as recognized by the settler state but as produced through “relationship to self and others.”[26] In thus quoting Indigenous theorists Mishuana Goeman (Tonawanda Band of Seneca) and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg), respectively, in constellation with Walcott, Black Shoals recreates at the level of theory the kind of activist coalitions King found during her time in Toronto. The maps of such coalitions, if they exist, require an errant cartography.

I don’t wish to force a close analogy between, say, Irishness and Canadian Blackness, or to minimize the differences between the experiences of diaspora among Irish subjects on the one hand and Black subjects in the Caribbean, the United States, or Canada on the other. At the same time, I share King’s sense of the importance of the counter-cartographic “between” in Walcott’s formulation—of how powerfully it can locate not just diasporic itineraries but also conditions of suspension, erasure, and mediation, as well as the prospect of new conversations and coalitions. What’s more, asking what non-geographical “betweens” might be traced in Ulysses can bring us to new questions not just about race and diaspora in Joyce’s book but also about how even its attenuated engagement with questions of Indigeneity might be located in relation to broader settler-colonial histories and itineraries. For example, how might we place a passage like this one from “Wandering Rocks,” focalized through Stephen, on the book’s map of Irish self-understanding?

Two carfuls of tourists passed slowly, their women sitting fore, gripping the handrests. Palefaces. Men’s arms frankly round their stunted forms. They looked from Trinity to the blind columned porch of the bank of Ireland where pigeons roocoocooed. (U 10.340–43)

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word paleface originated as a ventriloquism of Native American speech by white settler writers such as James Fenimore Cooper. Constructing the white settler as both the topic and the narrator of Native speech, paleface might be said to epitomize free indirect discourse as a settler colonialist practice. Cropping up in Stephen’s interior monologue, however, the word further analogizes settler colonialism in Ireland to settler colonialism in the United States. It does so by constructing British tourists in Dublin as white settlers in North America and, by extension, the Irish as American Indians.[27] Nor is this the first time paleface has featured in Stephen’s thoughts. It appears in “Telemachus,” when he imagines wealthy Oxford students hazing a boy named Clive Kempthorpe. “Palefaces: they hold their ribs with laughter, one clasping another. O, I shall expire! Break the news to her gently, Aubrey! I shall die!” (U 1.166–67). Within the context of that episode, it works in circuit with the Indigenization of the elderly milkwoman, whom Mulligan calls an “islander” to the paleface Haines, an Oxford man who assumes she is an Irish speaker (see U 1.393). The Gaeltacht, apparently, is located between Oxford and Dublin.

In the “Cyclops” episode, the Citizen seizes on the transatlantic settler-colonial analogy to point up Britain’s culturally genocidal attitude toward Irish famine migrants, attributing to the Times of London a slur for Native Americans that, like paleface, has its origins in American white settler discourse:

We have our greater Ireland beyond the sea. They were driven out of house and home in the black ’47. Their mudcabins and their shielings by the roadside were laid low by the batteringram and the Times rubbed its hands and told the whitelivered Saxons there would soon be as few Irish in Ireland as redskins in America. (U 12.1364–69)

On the heels of a clause about how famine migrants’ homes were “laid low by the batteringram,” the analogy between Irish and Native Americans is revealed to be a truncheon in its own right. The Citizen’s reference to the paucity of Indians left in America, meanwhile, implies that the aim of British famine policy, too, might not have been cultural genocide but genocide, period. The exterminative scene painted by the Citizen may seem unrelated to the subtler cultural dynamics Stephen evokes by thinking “Palefaces” to himself. But the two find a midpoint or relay in J. P. Mahaffy’s infamous description of the young James Joyce as “a living argument in defense of my contention that it was a mistake to establish a separate university for the aborigines of this island—for the corner-boys who spit in the Liffey.”[28] This from the Unionist Provost of Trinity College, Dublin, wielding the Irish-Indigenous analogy to place higher education for Catholics under racialized cancelation. The passages I’ve been tracing in both Stephen’s discourse and the Citizen’s take hold of analogies like Mahaffy’s to expose their rotten roots, their murderous ramifications.

But if we follow the lead of Walcott and King, we might also read the same passages as moments of countermapping that pull North America out of the offshore margins of Joyce’s novel and relocate it “between the U.K. and Ireland.” Why? Because the vocabulary of Irish self-understanding under British settler colonialism is routed, in these passages, through the cultural nerve-center of North American white-settler vocabularies.[29] This is obviously a very different kind of “between” from Walcott’s location of Canadian Blackness “between the U.S. and the Caribbean.” But like Walcott’s remapping it transforms what has formerly been understood as a marginal link (in Ulysses, North America) into a central hub. Not uncritically so, for by foregrounding white settler terms for both the Indigenous and settler groups involved in North American settler colonialism, these passages insist on Catholic Ireland’s linguistic and cultural complicities with that settler project. They insist, by extension, on Irish Americans’ and Irish Canadians’ having been the material beneficiaries of that project. But without ignoring the problematic terms in which it’s articulated, we can observe that the analogy between the two settler colonial projects is also a site of possible decolonial coalition across gulfs both spatial and ideological—witness the fact that Stephen and the Citizen, despite being at politically skew angles to one another, make that analogy in common.

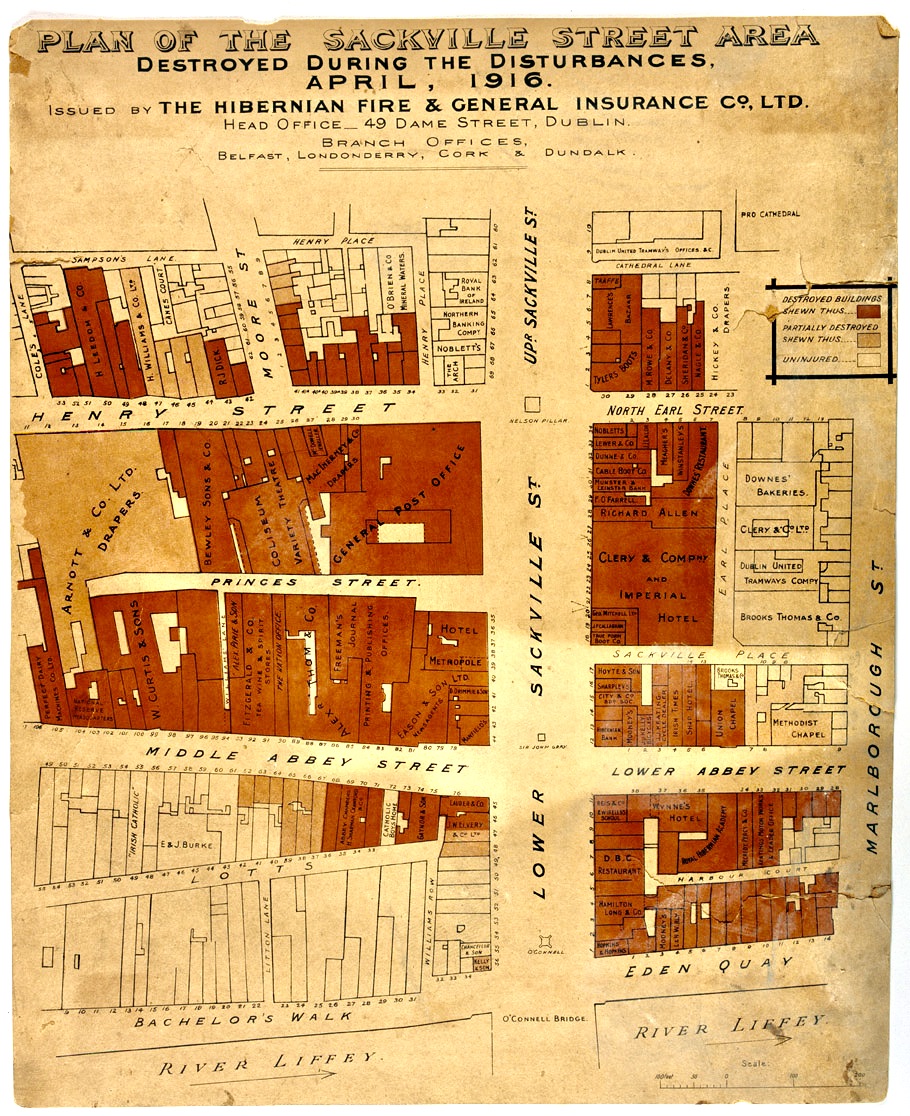

A second type of countermapping internal to Ulysses has to do with temporality. Enda Duffy has pointed out that in one of the “Cyclops” episode’s later interpolations, the course followed by the procession of saints is “precisely that from the center of the rebellion, the General Post Office on O’Connell Street [formerly Sackville Street], to Barney Kiernan’s, through some of the streets that were worst hit by British shelling” in the Easter Rebellion.[30] Duffy and other Joyce scholars have paired the passage with photos of the Dublin city center shelled to ruins by the British soldiers who put down the Rebellion. But an insurance assessor’s map of the buildings damaged in the Rising (Fig. 3) more precisely illustrates Duffy’s point about the countermapping Joyce does in the “Cyclops” passage. With orange denoting “partial destruction” and red simply “destruction,” this cadastral map—one focused on the delineation of individual properties—lays out the degrees of ruination street by street, parcel by parcel. Joyce’s procession of saints “wended their way by Nelson’s Pillar, Henry street, Mary street, Capel street, Little Britain street chanting the introit in Epiphania Domini which beginneth Surge, illuminare,” doing “divers wonders such as casting out devils, raising the dead to life, multiplying fishes, healing the halt and the blind, […] blessing and prophesying” (U 12.1719–26). To follow the itinerary of the passage while heeding its repeated references to raising and rising (“Surge, illuminare”) is to imagine a saintly procession wending its way, in a novel set in 1904, through a cadastral post-Rising ruin map from 1916. It’s to find in Ulysses a punctual text set on a single, actual day yet riven with subtle anachronisms.[31] Joyce’s countermapping reclaims spatial meaning from urban devastation. It also enacts a miraculous slippage in the gears of time.

Figure 3. Map

of the General Post Office and surrounding area, issued by the

Hibernian Fire & General Insurance Co., Ltd., showing buildings

destroyed or

damaged by fire during the Easter Rising of 1916.

National Museum of Ireland,

Digital Repository of Ireland, https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.w089fr674.

Other Cityful Coming

What would it mean to do justice to Ulysses’s countermapping in teaching and scholarship about Joyce’s book? The best I can do here is to speculate that it might mean telling stories that are no longer fixated on the book’s painstaking fidelity to the map of Dublin in 1904—stories that are instead about the cities named or implied by Ulysses, or about the forests or plains or deserts between Dublin and those other cities. It could mean remapping Dublin onto other cities, as Conor McGarrigle did with his Situationism-inspired JoyceWalks project in the 2000s, inviting the residents of Mexico City, Berlin, Jundiai, and Tokyo to take walks described in Ulysses after transposing them onto the maps of their home cities.[32] Such a practice, were we to revive it, would only become more resonant as international literary pilgrimages dwindle in a future where we’ve reduced carbon emissions by flying less. Alternatively, we could plug the year 1904 into the switchboards of other years and other urgencies, so that they, too, become unsettled in time and cast new shadows on Joyce’s book in turn. Imagine embracing anachronism as a refusal of standard-issue chrono-politics, reading Ulysses by the light of twenty-first-century Dublin maps of crime and gentrification, sewage and secularism.[33] Or imagine turning to non-geographical “betweens” as a rejoinder to orthodox carto-politics. We might at last learn to hear Bloom’s words in “Lestrygonians” as something other than a lament about the endless waves of death and birth in a single city—as, instead, a countermap of multiple cities strung loosely together in the dark, seen scrolling by through the window of an impossible plane: “Cityful passing away, other cityful coming, passing away too: other coming on, passing on” (U 8.484–85).